What's New

Looks Maketh Product: Evolution Of Trade Dress Protection

Author: Manavi Jain

Introduction

Brand owners are coming up with interesting and unique ways to create a lasting impression on the consumers, be it by way of packaging of the product or by uniquely designing the product itself. It is such peculiar features that are remembered and associated with the brand – sometimes even more readily than the brand name itself! Such is the power of get-up and appearances, (or what we call “trade dress”), when it comes to businesses. Naturally, on account of bearing such strong associative value, “trade dress” forms the subject matter of IP protection.

Trade Dress and the Trade Marks Act, 1999

Trade dress is not statutorily defined in India. A ‘mark’ is defined under Section 2(m) the Trade Marks Act, 1999 as:

“mark” includes a device, brand, heading, label, ticket, name, signature, word, letter, numeral, shape of goods, packaging or combination of colours or any combination thereof; (emphasis supplied)

From the above, it can be inferred that certain kinds of trade dress may overlap with and fall under the definition of a trade mark. For such trade dresses, a registration may be sought under the Trade Marks Act, 1999. For others (which do not squarely fall under the aforementioned definition of a “mark”), an action may still lie by way of a suit for passing off, as long as certain conditions are fulfilled.

Takeaways from Past Rulings

“The oldest and most traditional definition of trade dress was limited to the overall appearance of labels, wrappers, and containers used in packaging a product.”[1]

The following cases discuss the traditional notions of trade dress in India in the confines of the features/elements of packaging:

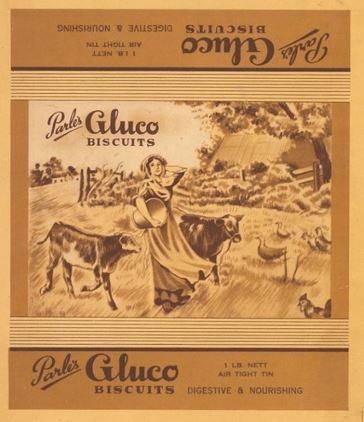

- Supreme Court made a few significant observations in its judgment in Parle Products (P) Ltd. v. J.P. and Co.[2], which discussed deceptive similarity in product-wrappers of competing biscuit brands. The Appellant’s wrapper (with its colour scheme, general set up and entire collocation of words) was registered under the erstwhile Trade Marks Act, 1940. Tabulated below are the specificities of the “wrapper” of the Appellant’s product as against that of the Defendant’s claims of minute dissimilarities thereof (as mentioned in paragraphs 3 and 5 of the judgement) – both products being biscuit packets:

| Appellant’s wrapper | Dissimilarities claimed by the Respondent’s vis-à-vis its wrapper |

| Buff ColorDepicted a farm yard with a girl in the center carrying a pail of water, with cows and hens around herBackground of a farmyard house and trees | Depicted a picture of a girl supporting with one hand a bundle of hay on her head and carrying a sickle and a bundle of food in the other handThe design of the building depicted is different The words printed on the wrapper are different |

Photo is for representational purposes only and is sourced from here

The Representative’s assertions as regards dissimilarities in the wrappers were accepted both by the Trial Court as well as the High Court of Mysore to conclude that a case for infringement or passing off is not made out. The Supreme Court, overruling the findings of the Trial Court as well as the High Court, held “…we find that the packets are practically of the same size, the colour scheme of the two wrappers is almost the same; the design on both though not identical bears such a close resemblance that one can easily be mistaken for the other. The essential features of both are that there is a girl with one arm raised and carrying something in the other with a cow or cows near her and hens or chickens in the foreground. In the background there is a farm house with a fence… Anyone in our opinion who has a look at one of the packets to-day may easily mistake the other if shown on another day as being the same article which he had seen before. If one was not careful enough to note the peculiar features of the wrapper on the plaintiffs’ goods, he might easily mistake the defendants’ wrapper for the plaintiffs’ if shown to him some time after he had seen the plaintiffs’. After all, an ordinary purchaser is not gifted with the powers of observation of a Sherlock Holmes. We have therefore no doubt that the defendants’ wrapper is deceptively similar to the plaintiffs’ which was registered.” (emphasis supplied).

- Delhi High Court’s interim ruling in the case of Colgate Palmolive Company & Anr. v. Anchor Health and Beauty Care Pvt. Ltd.[3], wherein, it was held, “It is the overall impression that customer gets as to the source and origin of the goods from visual impression of colour combination, shape of the container, packaging, etc. If illiterate, unwary and gullible customer gets confused as to the source and origin of the goods which he has been using for longer period by way of getting the goods in a container having particular shape, colour combination and getup, it amounts to passing off. In other words if the first glance of the article without going into the minute details of the colour combination, getup or layout appearing on the container and packaging gives the impression as to deceptive or near similarities in respect of these ingredients, it is a case of confusion and amounts to passing off one’s own goods as those of the other with a view to encash upon the goodwill and reputation of the latter… Colour combination, getup, layout and size of container is sort of trade dress which involves overall image of the product’s features. There is a wide protection against imitation or deceptive similarities of trade dress as trade dress is the soul for identification of the goods as to its source and origin and as such is liable to cause confusion in the minds of unwary customers particularly those who have been using the product over a long period.” (emphasis supplied).

Illustrative Cases: Evolving Scope of Protection

Trade Dress in the shape of a bottle

- In Gorbatschow Wodka Kg Vs. John Distilleries Limited[4], the Bombay High Court, while adjudicating on the issue whether the unique shape of the Gorbatschow Wodka bottle is eligible for trademark protection or not, observed that “…Section 2(zb) of the Trade Marks Act, 1999 defines the expression ‘trade mark’ to mean “a mark capable of being represented graphically and which is capable of distinguishing the goods or services of one person from those of others” and to include the “shape of goods, their packaging and combination of colours”. Parliament has, therefore, statutorily recognized that the shape in which goods are marketed, their packaging and combination of colours form part of what is described as the trade dress.” (emphasis supplied).

[Photo is for representational purposes only and is sourced from here]

Trade Dress in the get-up of a toy

- In Seven Towns v. Kiddland[5], the Delhi High Court was posed with the task of adjudicating upon the unauthorized use of the trade dress in the famous Rubik’s Cube [a cube consisting of 6 different coloured stickers namely particular shades of green, red, blue, yellow, white and orange]. While adjudicating on an application for interim relief, the Court decided in favour of the plaintiff and observed “The arguments of the defendants are that no exclusivity can be claimed in basic colors or the color black which forms the border/cage. The said submissions have no force as the plaintiffs are not seeking protection in any single feature but in the combination of all these features which constitutes the get up of a product namely the combination of shape/size/color-combination/black border of the squares etc…There is also no force in the submission with regard to black grid not being distinctive. The main question being considered was whether the trade dress is inherently distinctive. In order to compare the two products with regard to trade dress, the overall look and appearance of the products and general “impression & idea” left in the mind by the consumer is to be kept in the mind.” (emphasis supplied).

[Photo is for representational purposes only and is sourced from here]

Trade Dress in the get-up of a shoe

- In Skechers USA Inc & Ors v. Pure Play[6] , the Delhi High Court had to adjudicate a case where the subject matter was a shoe, with certain “identifying” unique features such as – positioning of responsive points on the sole of the shoe in distinguishing colors, light weight of the shoe, Side “S” logo of Skechers and “Goga Mat” being used in the cushioning of the inside sole of the shoe. A few photographs with the shoe of the Plaintiff (pink) as against the Defendant (black) are given below:

While adjudicating on an application for interim relief, the Court decided in favour of the Plaintiff and observed “…I am, prima-facie, satisfied that the visual impression gathered from the trade dress of the competing products is that trade dress of the plaintiffs product is substantially copied by the defendants which is likely to result in confusion. There is every likelihood that an unwary and gullible customer may get confused as to the source of origin of the shoes of the defendants, and may assume that the same come from the source of the plaintiff as the shoes of the defendants have a remarkable resemblance with those of the plaintiffs… the several aspects of trade dress are strikingly similar between the shoes of the plaintiffs and those of the defendants and the overall get up and trade dress is also markly similar…” (emphasis supplied).

Trade Dress in the get-up of a dinner plate

- In LA Opala R.G. Ltd. v. Cello Plast and Ors.[7], the High Court of Calcutta recognized the trade dress in the patterns on a dinner plate and held that “There is no doubt that the etchings or drawings on the rival plates look similar. The copying of the design is self-evident. All the essential elements of the trade dress, get up and design of the three plates of the petitioner have been copied by the respondent No. 1. It is quite apparent that the arrangements of the twigs, flowers, etc. are the same. The colour combinations are also, to a large extent, similar.” (emphasis supplied). Photographs of the competing products are reproduced below:

The Court also laid down some essential points in relation to enforcement of trade dress, viz., the three basic elements required to be established in a suit for trade dress infringement or passing off:

- Existence of a protectable trade dress in a clearly articulated design or combination of elements that is either inherently distinctive or has acquired distinctiveness through secondary meaning;

- Likelihood of confusion as to source, or as to sponsorship, affiliation or connection;

- If the trade dress is not registered, it must be proved that the trade dress is not functional. If the trade dress is registered, the registration is presumptive evidence of non-functionality.

Conclusion

With brands exploring the different ways in which a product can be presented, the Courts have been forced to expand and liberally interpret the scope of protection of trade dress. What started with recognition and protection in the elements of conventional wrapping/packaging of a product has now evolved to cover that and much more – and the process is still evolving. As long as the “get-up” in question satisfies the above-mentioned conditions, and is proved to be a source identifier, it may fall under the umbrella of protection as a trade dress.

[1] Storck USA, L.P. v. Farley Candy Co. 14 F 3d 311, 29 U.S.P.Q. 2d 1431

[2] AIR 1972 SC 1359

[3] (2003) 27 PTC 478

[4] 2011 (47) PTC 100 (Bom)

[5] I.A. No.13750/2010 in CS(OS) No. 2101/2010

[6] I.A. No. 6279/2016 in CS(COMM) 573/2016

[7] 2018 (76) PTC 309 (Cal)

Disclaimer: Views, opinions, interpretations are solely those of the author, not of the firm (ALG India Law Offices LLP) nor reflective thereof. Author submissions are not checked for plagiarism or any other aspect before being posted.

Copyright: ALG India Law Offices LLP.